Introduction to SEC-DED Algorithms: One More Step Beyond Basic EDAC

In the last article we talked about what happens when we want to be protected against single-event effects that can alter the information in our memory. We discussed the Airbus case, and we considered the situation where only one bit gets corrupted. We usually talk about single-event upsets — but what happens if more than one bit gets upset?

This is not a strange situation, and it’s called a Multiple Event Upset (MEU) instead of a Single Event Upset.

So the question for today is: what do we do if we want to be protected against those cases? Well, we start looking into something called Single Error Correction, Double Error Detection (SEC-DED). If you’ve read the previous two articles, this one should feel like a natural continuation — the “next layer” on top of what we already explored.

Let’s get into it.

A quick look at real spacecraft data

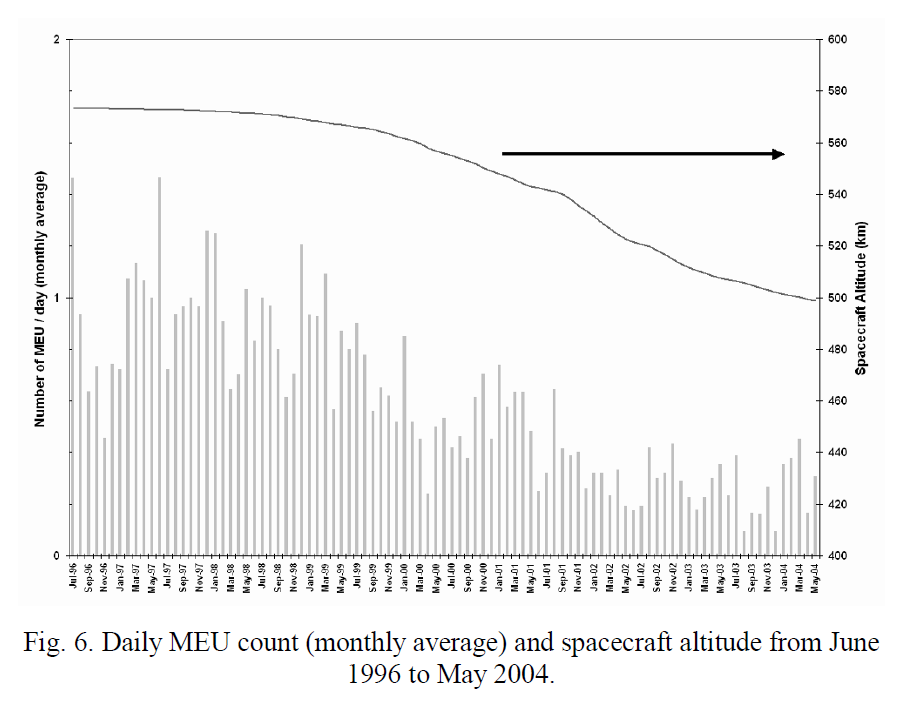

Before jumping into the algorithm, here’s some real flight data related to memory upsets. The plot below comes from:

“In-Flight Observations of Long-Term Single Event Effect (SEE) Performance on XTE Solid-State Recorders (SSRs)” Poivey, Gee, LaBel, Barth — NASA/GSFC

This plot shows how many memory upsets per day were recorded over eight years, along with the spacecraft’s altitude. Upsets happen continuously, and depending on where they land in memory, they may have no impact at all or they may affect something the system is using at that moment.

This is exactly the type of environment where EDAC techniques can improve the reliability of your system.

So what is SEC-DED and how does it work?

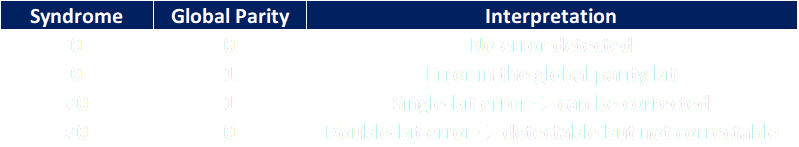

If you already understood Hamming(7,4), SEC-DED is almost the same thing with one small addition. You take the usual Hamming structure (which can correct one bit) and add one global parity bit across the entire codeword.

Even though this is a tiny change, it gives enough information to distinguish between:

no error

a single-bit upset (correctable)

a flip in the parity bit

a double-bit upset (detectable, not correctable)

A simple way to visualize the decision logic is:

If you want a bit more background on where all these ideas originally came from, a great complementary reference is Richard Hamming’s classic:

“Coding and Information Theory” — Richard W. Hamming

https://static.ias.edu/pitp/archive/2012files/Hamming_CHs1-3.pdf

It covers parity, Hamming codes, and the foundations of error detection in a very accessible way.

What we implemented in the simulation

To make this easier to visualize, I prepared a small Google Colab notebook where we:

encode data using SEC-DED

intentionally inject faults

decode the corrupted data

classify the result

The simulation steps are:

Generate a random 4-bit value

Encode it using SEC-DED

Randomly inject:

no error

one-bit error

two-bit error

Decode according to SEC-DED rules

Classify the result as:

corrected

detected (but uncorrectable)

or undetected

Repeat this thousands of times

This lets us see how often each situation occurs in practice.

What to expect from the simulation

Running 20 000 test cases produces three main outcomes:

1. Data decoded correctly

Most cases fall here — either because nothing flipped or because SEC-DED repaired the single-bit upset.

2. Data decoded with errors but correctly flagged

These represent the double-bit upsets. The algorithm can’t fix them, but it can detect them.

3. Data decoded incorrectly with no detection

These are rare corner cases. Every EDAC technique has configurations it can't uniquely distinguish, so it's interesting to see how often those appear.

The goal is not to declare SEC-DED “the best approach,” but simply to observe its behavior and understand its strengths and blind spots.

Strengths and trade-offs of SEC-DED

Strengths:

corrects all single-bit errors

detects most double-bit errors

extremely simple and lightweight

requires minimal storage overhead

Trade-offs:

cannot correct double-bit errors

cannot detect every possible multi-bit pattern

requires system-level decisions for flagged errors

Like any EDAC technique, SEC-DED is simply a tool.

It’s useful in some architectures, unnecessary in others, and one of many available options.